All His Ghosts Must Do My Bidding, 2019 installation view. Photo: Jay Parekh

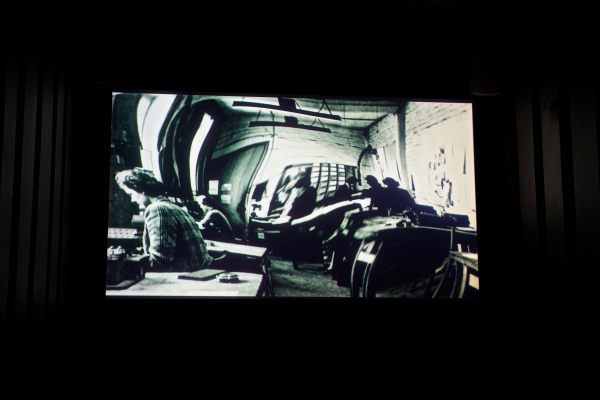

Morgan Quaintance, Missing Time, 2019

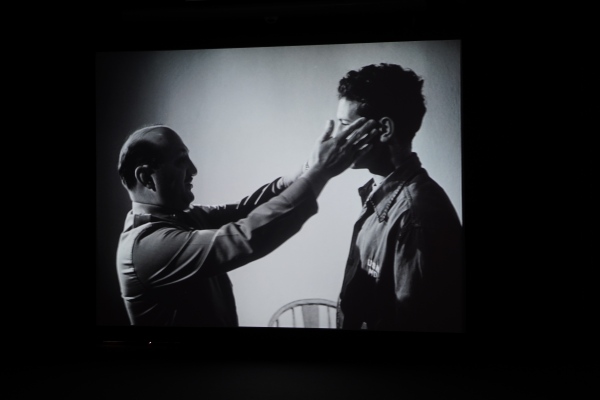

Pallavi Paul, Acts, incitements, etcetera, 2019

Published: Art Monthly, September 2019

All His Ghosts Must Do My Bidding

Wysing Arts Centre Cambridge 7 July to 25 August

The master sorcerer goes out, leaving his apprentice alone to clean the workshop. Now, at last, the apprentice can call on the master’s spells and says, ‘All his ghosts must do my bidding’. In Johann von Goethe’s original 1779 Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the master returns and restores order after the apprentice wreaks havoc, but in the version curator John Eng Kiet Bloomfield imagines, there is no master, the apprentice is free to experiment without restriction, free to unleash chaos. Marking Wysing’s 30th anniversary, this alumni show, featuring 16 artists from previous exhibitions and residencies, considers ‘art as magic, artists as magicians, and the studio as a magical site’, asking who gets be the sorcerer, if no one needs to be the apprentice.

If we think of art as magic, it is no longer simply a vehicle of meaning, it becomes something with agency, consciousness and desire, intelligence and intention, as WJT Mitchell says in the 1996 essay ‘What Do Pictures Really Want?’. Stuck on the reception windows, Olivier Castel’s postcards outline plans for various installations across Wysing, never realised because they were too expensive or large-scale. Tools for Wysing (Messages to the Public), 2014-2019, for instance, pictures a screen in a field drawn in colour pencil. Then, below, a written note proposing to install one of Jenny Holzer’s luminous Times Square billboards in the north-eastern field. A scattering of salt beneath the postcards suggests transformative potential, as if Holzer’s billboard might be conjured into Cambridgeshire’s greenbelt. Melika Ngombe Kolongo’s 2018 audio installation Resonance (Forced Vibrations) draws on Bantu-Kongo cosmology. Photos perhaps of a lunar surface hang from the ceiling, like satellites, catching otherwise inaudible celestial murmurings. Rumbling, whirring, spiralling tones beckon you to the astral plane. Mounted on a wooden structure in the gallery, Phil Root’s painting Ten of Wands, 2011, depicts a figure, maybe an artist in the studio, struggling to cling to a bunch of battening, as if picturing the making of the painting’s wooden support, a haunting proleptic image. It’s as if the artist had been cursed, forever stuck spellbound inside their own painting, always never finished. Root’s work suggests that artists don’t lead the enchanted lives suggested by the exhibition. The studio doesn’t exist outside the constant pressure to make money, to produce, to strive and to achieve.

Goethe’s titular character is explicitly male, but the masters of ‘All His Ghosts’ are women, they fill the history books and art history’s canon. W.I.T.C.H, 2015, Anna Bunting-Branch’s series of hand-painted posters are inspired by the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell, a name under which various groups of American feminist activists united in the 1960s. They dressed up as witches, a figure of long-standing persecution and paternal panic – the ‘original guerrillas’, according to the group’s 1968 manifesto. They protested against patriarchy and capitalism, hexed Playboy and Wall Street bankers. ‘We Invoke the Culture of Heretics’, ‘Wild Imaginations Transform Chauvinist Hegemony’, read the posters’ rallying cries. Projected in a room painted deep red, Heather Phillipson’s video WHAT’S THE DAMAGE, 2017, hails man’s Last Judgement. ‘Let us pool our monthly frenzy. Drown the jerks in menstrual debris,’ voices chant, a call for mass-mobilisation, like the W.I.T.C.H posters. While six-packs, erect dicks, a bare-chested Putin on horseback, a peroxide-blonde hairpiece, and the rest of what the narrator calls ‘the infinite patriarchal circle jerk’, burst into flames and disappear down a bloody whirlpool.

The title of Elizabeth Price’s black and white film THE TENT, 2012, references James Moyes’s never-realised installation Vibration Tent, an environment in which to experience intense white noise and light, first described in a 1972 catalogue on the geometric art of the British Systems Group. Quotes from the book’s essays fade in and out in while a hand flicks through the photographs of works, exasperated by the stifling formalism and highfalutin declarations about art and politics. Then, ‘Boredom’ by the Buzzcocks breaks out and scissors snip the book’s bindings, cutting ties to Systems art, rejecting any artistic lineage. Jill McKnight’s radio play In The Balance, 2019, features a string of stories told by different characters for which McKnight produced a series of corresponding sculptures. One looks like some kind of quadruped, struggling to support its immense mass. McKnight tells listeners it is made from steel bequeathed to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park by Anthony Caro, who in turn inherited it from the sculptor David Smith. McKnight interrupts sculpture’s heavy-engineering circle jerk.

McKnight talks about her family as well as artistic roots, the working-class women who never got to be artists. Everyone said her Nana Phyllis could write a best-seller. ‘What does it mean to have a best-seller in you but to never write?’, McKnight asks Laure Prouvost’s 2013 film Grandma’s Dream poses the reverse question. Prouvost imagines her grandma had been artist, forming a counterpart to Wantee Prouvost’s 2016 film about her conceptual artist grandfather. ‘In Grandma’s dream, Grandad wouldn’t be an artist. Grandad would stop everything for her’, says a soft child-like voice as clouds drift by and water glistens in the sunlight. She’d be the protagonist of her own action story: “the police would be looking her” – a siren sounds in the background. “Conceptual art would do the dishes,” the voice adds, reflecting on how domestic labour is still largely gender and class divided.

Tai Shani’s sculptural installation Showings, 2018, is scatological, sensual. There are cylinders of extruded flesh, fingers stroking scarlet-coloured petals and a miniature bust of the anchorite Julian of Norwich, the medieval mystic and earliest known woman to write a book in the English language. They are set on three tabletops shaped like Aztec pyramids. Women are the architecture and architects of grand civilisations, their desires, bodies, histories like founding blocks.

Projected inside a cavernous, black shipping container, Pallavi Paul’s film is about forgotten women’s histories and women as repositories of secrets and untold stories. Acts, incitements, etcetera (2019) features audio interviews with women who worked at Bletchley Park during the Second World War. Women tend to appear in the addendum to histories of wars, but in Pallavi’s work they are protagonists. Similarly, Missing Time, 2019, by Morgan Quaintance is about collective amnesia, government secrets and national identity. Quaintance interweaves seemingly incongruous images and sounds, archive footage and digital video: alpine scenery, yodelling music; CCTV cameras and MI6’s HQ; and a US Cold War hypnosis programme. Together, it represents a kind of UK-transatlantic politico-historical unconscious. The last part of the film takes the form of a history documentary, a narrated presentation of the events following Britain’s withdrawal from Kenya. As artist* Simnikiwe Buhlungu describes, conflict broke out between the colonial administration and revolutionary forces, who British soldiers interned in concentration camps and subjected to extreme abuse. Many of the records were either destroyed or hidden. Today, as Buhlungu suggests, British identity preserves some histories of violence and represses others, celebrates WWII, the fight against fascism but buries colonial genocide in the deep recesses of its unconscious.

Neocolonialism uses the same kind of mental slide of hand. Imran Perretta’s 2019 sound installation The War On Terror makes use of an effect called the Shepard tone, which gives the illusion of a constantly ascending or descending tone, providing sustained tension. A haunting whirring, overdubbed by pounding bass and screeching strings, fills a small dark sound studio. You hear it in the sort of movies which usually begin with news footage of 9/11 or the 7/7 bombings, offering no historical or ideological context for seemingly unprovoked attacks. CIA or MI6 operatives are then sent to carry out so-called justice, extrajudicial executions and other atrocities.

Sometimes it is hard to follow Goethe’s ballad through the exhibition. And many of the works more readily fit under the rubric of psychology, mysticism or hauntology than magic. But it shows Wysing’s unequivocal commitment to supporting artist experimentation over the years and that it has been an artist-led space of alchemy that ‘All His Ghosts’ imagines.

*In the print version of this review published in Art Monthly (AM429), Simnikiwe Buhlungu was reffered to as a "historian"; Buhlungu is in fact an artist.